by Wes Jamison

Portraiture used to be mimetic, representative of the actual human stuff sitting before the painter. The belief was that a person’s essence, their subject, the spirit correlated directly to the uniqueness of their face. We believed in physiognomy and phrenology: Chaucer’s Summoner’s narrow eyes, black scabby brows, and whelks of knobby white or Whitman’s animal will and large philoprogenetiveness and size.

That is, we once believed we were a united thing, body and self—an incorporeal being nonetheless wrapped in flesh. Then some insufficiently Surrealist portraits caged that same being and tested the flesh, pulled it taught and almost transparent.

The first time I could have seen Francis Bacon’s work was in Tim Burton’s Batman: the Joker and his cronies break into the Gotham City Museum and knock over, spray paint, stab sculptures and paintings, vandalizing almost everything. Joker sees one of his knife-wielding henchmen approach Bacon’s Figure with Meat (1954): he raises his cane to stop the slashing knife and says, I kind of like this one, Bob. Leave it.

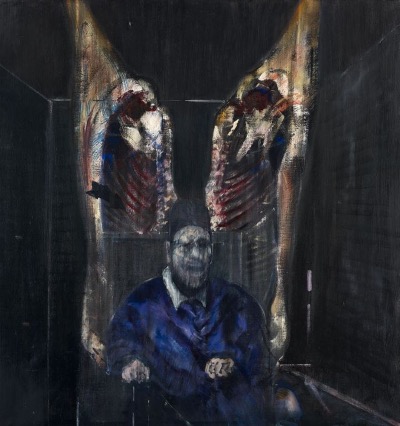

I stood, three times, in front of this oil painting, displayed in the Art Institute of Chicago. It depicts Pope Innocent X, seated, framed by racks of meat. His face is—what? Not unclear, exactly, but distorted and made imprecise by brush strokes and hues. Representative, perhaps; almost indiscernible. The Institute describes Bacon’s figures as tormented and deformed.

*

Early in our development, we establish a neural template for a face and for everything else, too. Any of these templates may be broken, misused, or deviated from. We adapt to this. But we simply cannot ever bear a violation of our templates for a body or, especially, a face. That is, we cannot adapt to or accept a violated body or face. It’s a threat to identity, our own—the epitome of what Julia Kristeva calls the abject.

As if victims of some violence, Bacon’s figures have also been described as disfigured and mutilated, pitiful and terrifying.

*

I used to believe in the phrase I think, therefore I am, thought I knew what it meant for Descartes, this phrase that became our Western ideal of mind over matter. Who you are is a thinking thing, not a physical thing; and that thinking thing, our minds, consciousness, or reason, has primacy over the physical thing, the body, the stuff. Moreover, our thinking things—our selves—do not exist in relation to anyone else’s thinking thing, precisely because they are ethereal.

I thought I could reason on my own, without you.

Psychoanalysts wouldn’t fall for Chaucer’s characterization, and many, like Kristeva, refuse to exactly follow our Cartesian heritage of the self, identity, the soul—any of it, whatever we call it. K disagreed on two points. First, she insists that subjectivity is an open system. When we people connect, there is an exchange—a pulsing of energies, desires, memories; we apply our energies to another and manipulate each other’s energies. Second, she insists in many ways and many times that the body is a requisite for the self.

Instead, these theorists all look to a short few months of our infantile development, between breastfeeding and speaking, as the time during which we develop our subjectivity, begin to exist as subjects, as selves.

Caillois and Schilder say we cannot develop a continuous sense of self until we can develop that spatial comportment: we cannot know who we are until we know where we are.

Freud says our ego, at this time, is a mental projection of what we see in the mirror: we are our surfaces, flesh and clothes.

Lacan says the baby sees a whole baby in that mirror, but that image of a self is alienated from my self. We only ever perceive ourselves in bits and pieces, so we are fragmented, and the mirror lies to us. That dissonance sees us conjure a fantasized image of wholeness that we can never achieve.

Yes, and. K says, during the same time, the baby turns away from the nipple during nursing, creating, for the first time, a disunity between itself and its mother. That is, our mothers are not us, and our mother is there, that, so what are we if not that, there.

I’ve seen Reddit arguments about the ableism and heteronormativity inherent in all these ideas. The responses vary wildly, but at their core is this weak and timid assertion that the problems are manufactured by the reader, the student, the critic: the mirror is not (necessarily) literal, the fragmentation is (hopefully) unreal, there doesn’t have to be a nipple, much less a mother.

*

I first tried learning K because a boyfriend told me I’d lover her work. Later, I tried reading her work because so many people around me told me I was supposed to. The first and greatest challenge to my understanding was reckoning with the fact that, even though they all told me that Powers of Horror is a theory of abjection, it is not. It is, instead, part and parcel of—in fact, the conclusion to—a theory of subjectivity, the subject, our essence.

K started developing her theory of selfhood, of subjectivity in her first book, Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, and it wasn’t fully developed until eleven years later, when she published Powers of Horror. Whatever I thought abjection was—whatever I thought that word meant at the time—what I came to understand after struggling through the book was rhetorical or grammatical or algebraic.

There is this thing called abject, which is neither object nor subject. Okay, but how? Certainly we are always the painter or the painted—everything around us, painted.

*

The first chapter, “Approaching Abjection,” is the most cited. It begins with her poetic impasto of the abject, which remains undefined, and ends with a description of its applications in religion and in the works of Dostoyevsky, Proust, and others. At its end, K refers back to this chapter as a phenomenological preliminary survey of abjection which will be given, in the next chapters, a more straightforward consideration.

Perhaps we choose to cite work that is intentionally imprecise, distorted, or admittedly unclear because, after page fifteen, the text becomes too difficult. Perhaps I was not the only one unprepared for K, opening this notorious book with only my Wikipedia knowledge and supported only by a collective knowledge that everyone knows Kristeva. Her writing, especially in this chapter, is difficult: her prose is a net of aphorisms and anaphora made almost indecipherable by the strings of appositives in virtually every sentence. Perhaps we cite these pages precisely because her sentences are equivocal. Take the very first in PoH:

There looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being, directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable. It lies there, quite close, but it cannot be assimilated.

A revolt is directed against a threat. But is it the revolt or the threat that is ejected. And from what. Is it the threat or the revolt that cannot be assimilated. Or, worse, is she using the journalist’s comma to elide what always seem to me essential words—not saying that the threat is ejected but that the threat is of something that has been ejected.

From the rest of the book, I know now that what lies quite close is the abject, and I know that the abject is threateningfor this very reason. Adjective, not verb. We’ve ejected the unthinkable, and we revolt against its continued proximity to us.

I still don’t know what a violent, dark revolt of being is, what this is doing looming within abjection, or what the subsequent comma is doing. But I think it has something to do with the Pope.

*

Portraiture is no longer a reflection or projection of our subjectivity. Bacon’s, a parody: their blurred moving faces cannot be contracted into a single form by our eyes. He demanded they be displayed behind glass, forcing us to bob our heads like birds to avoid any glare as we approach the art.

Our wholeness, as in the mirror, is only made possible by the gaze of the other. So these distorted, fractured, fragmented faces, unable to be understood properly, fail to become whole, subject.

So when we face them, there is no gaze, no eyes or face through which we are seen. So, we also fail to become whole, subject.

In a Bacon portrait, flesh is proven to be not only stretched taught over something that churns but also is itself churning. Our flesh, our language breaks and still nothing shows up to reassure us. We abject in the face of these—identity, an impossible matter.

We are always already exactly as fragmented as they.

Wes Jamison is the author of Carrion (Red Hen Press, 2024) and and Melancholia (Essay Press, 2016). They earned an MFA in nonfiction from Columbia College Chicago and a PhD in English from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.