by Rebecca Fish Ewan

My first impression of Iceland formed in 1980, my college freshman year, when I learned in geology class that Iceland was the youngest land on Earth. Young in the sense that new ground emerged from a molten womb all day and every day without end. I yearned to visit this infant place. It took thirty-six years to realize this desire and by then I had heard that people lived there too.

To prepare for my trip to Iceland, I bought a map and a small stack of books—The Sagas of Icelanders, Halldór Laxness’s Independent People, Oddný Eir’s Land of Love and Ruins, Eva Heisler’s Reading Emily Dickinson in Icelandic, Alda Sigmundsdóttir’s The Little Book of Hidden People and The Little Book of Icelandic, as well as the Iceland Pocket Guide. I listened to bits of books read in Icelandic, tried to learn phrases and words, hoping to find an occasion on my travels to say bergmálor sindrandi, words for echo and shimmering that seemed to emerge from the landscape like magma. I was convinced that the best way to get to know a country was through its landscape, literature and language.

I only travelled there for ten days and have been back home for over two years, yet I still believe in this trio of l’s, but would add a cautionary note about fetishizing a nation based on its history and myths.

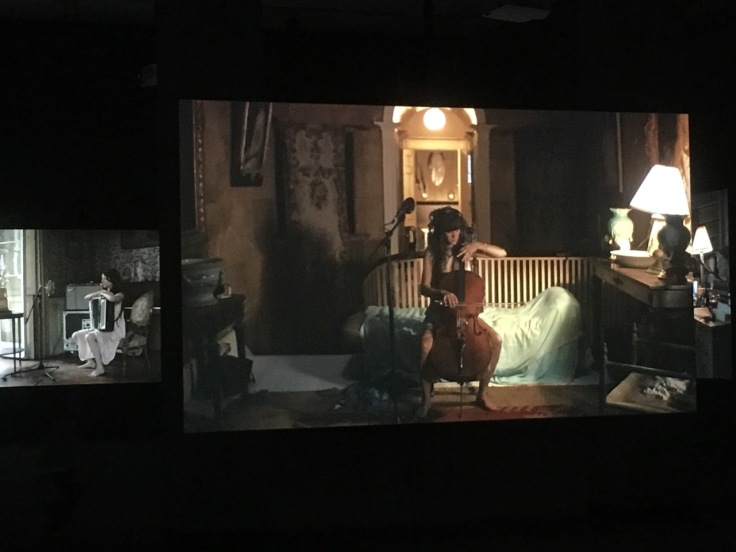

Last week I went to the Phoenix Art Museum to see the Ragnar Kjartansson’s exhibit Scandinavian Pain and Other Myths. I sat in a dimly lit space as nine videos projected on screens, musicians isolated in rooms of an old mansion playing as an ensemble through the miracle of technology. They eventually came together in real life and walked off into a bucolic landscape, still singing and playing music. An old man exploded a cannon. A dog followed them into the woods. This piece is called The Visitors, which makes sense since the artist was visiting the United States when he made it at a mansion, one of many in the Hudson River Valley. The landscape looks like it was painted by Thomas Cole. As I sat watching this story unfold, listening to the haunting refrain of Ragnar Kjartansson’s ex-wife’s poetry—There are stars exploding around you and there’s nothing, nothing you can do—sung by the musicians as they played a banjo, cello, accordion, guitars and piano, I wanted them to be in Iceland.

And not just any Iceland. The one in my culturally frozen fantasy full of Vikings, elves and steaming pastures. Even after a trip around the island nation, I went to the exhibit expecting to see Icelandic art that, of course, was created in Iceland by Icelanders and would include snow, sheep and sorrow. Viking horns. Huldufólk. Hot blue water. The midnight sun. Puffins. Hákarl and brennivín.

This is what I love about art. Visual art. Literary art. Hybrid art. Sonic art. Any kind of art has the potential to challenge our prejudices and stereotypes. Ragnar Kjartansson’s work reminded me to question my expectations and to recognize the lenses through which I perceive people, in art and in real life.

I went home and read Waitress in Fall, Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s poetry collection recently translated into English by Vala Thorodds. I picked the book because I wanted to read poetry by a living Icelandic woman. Something to offset the hypermasculinity of the verse in The Sagas of Icelanders that echoed in my head as I watched the Ragnar Kjartansson videos. The publisher of the collection, Carcanet, describes Kristín Ómarsdóttir as thriving “in the Vanguard of Icelandic literature,” and the collection includes poems from seven books, spanning thirty years.

At first, I read the book like I visit an art museum. I read it from end to end in silence. As I read, I placed a stickie note on the pages with poems that moved me most. Fire. Stove. Rain Days. Heyday. Ode. Then I returned to just these poems, like I return to favorite paintings in a museum. I lingered with them, read them a few times.

Then I did something I’ve never done before.

I’ve been experimenting with ways to free myself from my dependence on concrete reality by drawing while listening to music. My theory is that music taps into the place deep in my paleomammalian mind where memories and magic dwell, so drawing under the influence of sound will help me reach beyond the superficial veneer of what’s visible. It’s the way I used to draw as a kid before my brain hardened. It’s how I’d like to draw from here on out. To approach this practice with Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s book, I read the poems out loud into the memo app on my phone, then played them back as I drew and painted. In a perfect world, I’d listen to Kristín Ómarsdóttir read her own poems in Icelandic and I’d totally understand them, but this is never going to happen, what with the brain-hardening and all.

Reading poetry aloud places it in the mouth where it belongs. Poetry is a sonic medium. What I couldn’t fully grasp in the silent readings was the texture of the language, but it’s there nonetheless, which is a triumph of this translation. Spoken Icelandic sounds like water fluttering from a gully. I couldn’t understand a word of it on my visit to Iceland, but loved hearing people speak as I travelled around the watery country. Before my trip, I had thought the land only formed by fire, but water oozes out of its pores. It surrounds it. Rests on it like giant glacial paperweights. And it pours from the tongues of its people. As a water lover, I reveled in the fluid sounds of the language. I felt this in speaking Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s poetry, even though I spoke in English.

Still, there’s the urgency to tell you what her poems are about, but I don’t want to. The publisher says the collection is about the “lush mess of actual life, in its hands and fingers, lemons and clocks, socks, soldiers, snow, knives, mothers, nightstands, sweat, and crockery.” I would agree with this. In reading the collection I felt I was witnessing time passing in a woman’s life, the quiet ordinariness of it, yet also the passion and the rage that dwells underneath the day-to-day. Another refrain sung in The Visitors—Once again I fall into my feminine ways—echoed as I read. By spending time watching a naked man sing in a clawfoot tub in The Visitors before reading Waitress in Fall, my eternal gender debate was cranked up to eleven. I kept thinking what I’ve spent my life thinking: what the hell are feminine ways anyhow? Do all women have to write about their kitchens? Contrarily, is it permissible for women to write about their kitchens? Where do I stand on what women should write about?

Where do I stand? I stand beside her in her choices, that’s where.

The world is ready, beyond ready, to listen to women. To read their poetry. Hear them sing their own songs. Choreograph their own lives. To be heard.

At Þingvellir, beside the rift where land is born, men used to stand on a rock and recite the laws of the fledgling society from memory. The Sagas of Icelanders are filled with tales played out in this landscape where tradition coupled with new beginnings in a strange mixture of violence and civility. This place seems to speak the common language that I heard in both Ragnar Kjartansson’s art and Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s poetry, that of the messy day-to-day of being human in a land steeped in myth.

Then again, maybe that’s just me being a tourist again, wanting Icelanders to stand on rocks telling their stories and singing their songs while the earth births itself at their feet.

Rebecca Fish Ewan is a poet/cartoonist/writer & founder of Plankton Press, where small is big enough. Her hybrid-form work appears in Brevity, Punctuate, Under the Gum Tree, Mutha and Hip Mama. She teaches landscape architecture at ASU. Her books: A Land Between and new cartoon/verse memoir, By the Forces of Gravity.