by Kimmo Rosenthal

I was fortunate several years ago to see Francisco Goya’s series of etchings, Los Caprichos, in person at the Hyde Museum in Glens Fall, New York. I only had a passing acquaintance with Goya’s work, yet I was immediately taken with these strange, satirical, at times macabre works commenting on the darker side of human nature. Capricho, as one might guess, is a caprice, a whim, a play of the imagination. (I have since learned that Goya was inspired by Tiepolo’s capricci and scherzi, interestingly also done later in life as his work became increasingly darker and abstract, a far cry from the beautiful angels and colorful Tiepolo skies.) Similarly, Goya’s paintings became increasingly darker and more nightmarish as Los Caprichos were followed by the series Disasters of War and then his so-called Black Paintings.

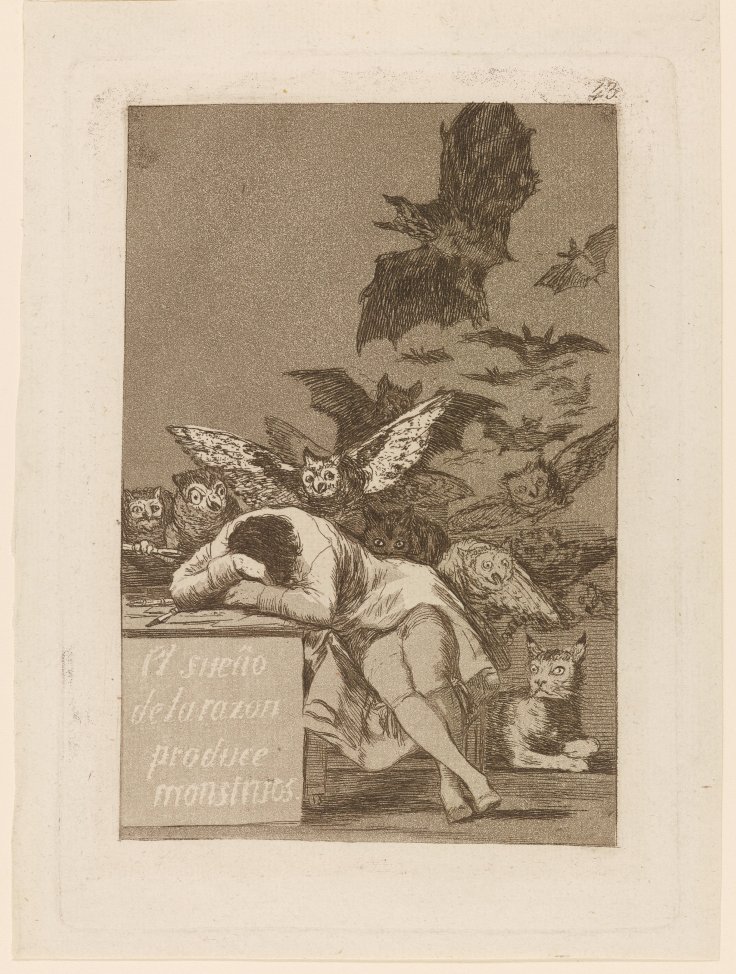

For me, the most compelling etching was also the most famous one, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. It was intended to be the frontispiece for the whole series. A man has fallen asleep at a desk with pencil and paper at hand, while he is surrounded by a row of owls. In antiquity, owls represented wisdom and knowledge (being associated with the goddess Minerva) and today we speak of them similarly. Interestingly, in Goya’s day in Spanish folklore the owl represented ignorance. There is also a horde of bats, evil, frightening creatures of the night, hovering in the background. The seated figure is said to represent the artist himself, yet I found myself thinking of Edgar Allan Poe, dreaming of the tell-tale heart or the masque of the red death.

The most compelling interpretation of the image is that when we sleep our rational faculties no longer hold sway, allowing the subconscious to emerge to the fore, unleashing its “monsters” that are held at bay during our diurnal existence. While sleeping, our minds might engage in a struggle with our darker emotions and inclinations, as well as the dread that is suppressed during our waking hours. We all have undoubtedly experienced this. However, Goya suggests in Los Caprichos that we are not just dealing with oneiric “monsters,” but rather that when reason is abandoned and the moral order collapses the mendacious and malefic aspects of human behavior gain a foothold. He sees himself surrounded by lust, gluttony, cruelty, and corruption, and political leaders and sinful clergy do not escape unscathed from his bilious etchings.

The ambiguity inherent in the phrase The Sleep of Reason makes it susceptible to alternative interpretations. I was musing over this earlier this year as I happened to be looking at a postcard of Goya’s etching while immersed in reading Nightwood, Djuna Barnes’ strange, dark masterpiece, which left me both intrigued and bemused. Only upon reading her other work and then rereading Nightwood did I begin to comprehend its themes better, and I began to relate it to Goya’s etching. (The postcard had remained nearby on my desk as I was writing down notes.) Perhaps too much “reason” or, if you will, adherence to always exhibiting “reasonable behavior” and conforming to societal norms and expectations can induce a kind of waking torpor, a state leaving the weak susceptible to the lure of the forbidden, which is a central theme in Barnes’ work. T. S. Eliot’s description of the essence of Nightwood in his introduction could just as well be about Los Caprichos. “The deeper design is that of the human misery and bondage which is universal.”

Barnes wrote Nightwood to exorcise the aftereffects of her doomed love affair with the actress Thelma Wood, who betrayed and abandoned her. The main protagonist of Nightwood, Nora Flood, who is Barnes’ alter-ego, sinks into a deep state of melancholy and ennui, as she is unable to comprehend the transgressions of Robin Vote (who represents Thelma), who, seemingly overtaken by a thirst for the forbidden, has succumbed to depravity without exhibiting any remorse. Robin is unable to find meaning and sustenance in her relationship with Nora and, failing to do so, she is unable to resist becoming beset and overwhelmed by darker passions.

Central to Nightwood are the raving, unhinged monologues of the Doctor, who acts like a Greek Chorus commenting on the action, and, if it is possible, presents an even bleaker view of humanity than Goya does in his Caprichos. Both bring to mind one of Kafka’s Zürau aphorisms: in a certain sense, the Good is comfortless. The Doctor describes humans as being “continually tried by the blows of an unseen adversary.” They develop a sense of hopeless estrangement from living out their lives in an ordained, predictable fashion with their personal relationships adumbrated by the inevitability of failure. A struggle ensues between “reason,” or what is deemed appropriate, and the lure of transgressing and giving oneself up to the dark side of the soul. Robin Vote highlights this struggle when she visits a church, presumably seeking redemption and atonement, only to return to her room to read the Marquis de Sade.

In the chapter “Watchman, What of the Night?,” Nora Flood seeks out the Doctor to try to understand the events that are unfolding around her. He offers no consolation. In discussing the essence of the night he opines “every day is thought upon and calculated, but the night is not premeditated.” His pronouncements, such as “we are full to the gorge with our own names for misery,” could be used to articulate the sentiments behind Goya’s Caprichos. Once exposed to the darkness of the night, people can never again live the life of the day. His rambling outpourings become darker, claiming that given an “eternal incognito with no thumbprint against our souls,” we would yield to depravity. Abandoning the constraints of reason results in condemnation to “drinking the waters of the night at the waterhole of the damned.” There is no prospect of assuagement nor of transcendence.

It might be easy to ascribe Goya’s ill-tempered, contrarian views to being a product of historical context with Spain still in the throes of darker ages, the Renaissance not yet having arrived there, as the church and the powerful and corrupt nobility still held sway. The belief that there is a timelessness to the assertion that The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters is validated by the fact that throughout history transgression of the accepted moral order has been in evidence. The news today from around the world makes us realize that reason is dormant, if not on the verge of being vanquished in its sleep, and the concomitant “monsters” are all around us.

The Doctor’s final pronouncement in Nightwood expresses the end result of this sleep of reason we are experiencing. “Nothing but wrath and weeping.”

References

Djuna Barnes, Nightwood, New Directions, 2006 (with Foreword by Jeanette Winterson and Introduction by T.S. Eliot).

See Robert Hughes, Goya, Knopf, 2003, for an illuminating discussion of Los Caprichos and Goya’s late period.

Kimmo Rosenthal, after a long career of teaching and publishing mathematics, turned his attention to writing. He has over forty literary publications and a Pushcart Prize nomination. Recent work has appeared in Tiny Molecules (Observations), The Fib Review, After the Art, BigCityLit, and The Ravens Perch.