by Jehanne Dubrow

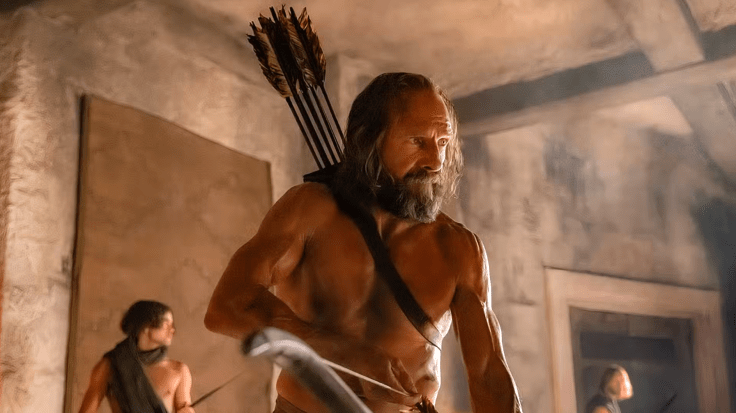

In The Return, a recent cinematic retelling of The Odyssey, the opening shot shows us Telamachus who stares out at a violent ocean, perhaps thinking of the father he can’t remember. Then we see a loom threaded with a wound-red warp and a wooden shuttle whose curved shape echoes that of a small boat. This is Penelope’s domain. And, finally, Odysseus appears onscreen. He’s naked, washed ashore and still unconscious, the wreckage of a craft drifting in the water behind him. From its first moments, we understand that this this will be a movie about homecoming and the people most devastated by the aftermath of war.

Studying the classics in college, I loved the first modifier Homer uses to describe Odysseus, πολύτροπος, meaning that the king is someone of “many turns.” In her recent translation, Emily Wilson goes with the provocative choice of “a complicated man.” And, yes, trauma is complex. God-plagued, pursued by nightmares of war, Odysseus weeps by the water for a home he cannot reach. He keeps turning, twisting, trying to find a way to Ithaka. And when he eventually arrives on the island, he comes disguised as a beggar, not realizing that even without the concealment of rags he has been transformed by a lifetime of wielding a sword and watching others die.

The word “trauma” is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root “tere-,“ which means “to rub, turn.” Other words that come from the same root include thrash, thresh, throw. Also detour and return. Also thread. The man of many turns is a figure of trauma. Home is a distant point on a map.

I’ve spent the last two decades thinking and writing about how these literary characters speak to the conditions of my own ordinary marriage, my husband’s twenty-year career in the Navy, how seldom we saw one another until he retired in 2019, what it might mean for a real woman to possess Penelope’s impossible faithfulness. Once, a poet at a writer’s conference chastised me for presuming to speak in the voice of the queen. “A modern military marriage has nothing in common with The Odyssey,” he scolded me. He was indignant that I should see myself in Penelope. Yet this, I believe, is what The Return asks of its audience: to find ourselves in the tired, creased faces of these actors. The characters are not guided by gods. Their trauma is modern and slow-moving.

In his book, Mimesis, Erich Auerbach famously describes The Odyssey as a text in which all is “[c]learly outlined, brightly and uniformly illuminated, men and things stand out in a realm where everything is visible and not less clear—wholly expressed, orderly even in their ardor—are the feelings and thoughts of the persons involved.” The approach of The Return is far more internal. Scenes often favor gestures over dialogue. When characters speak, their words are clipped of poetry. Auerbach observes that “the Homeric style knows only a foreground, only a uniformly illuminated, uniformly objective present.” Much of The Return is filmed in half-shadow. Characters stand in corners that flicker with firelight. The camera shifts its perspective from Telemachus to Penelope to Odysseus, so that the audience can experience how each person has been uniquely wounded by war, distance, and absence.

Meanwhile, most of the suitors in the movie are beautiful, their bodies muscular and smooth. They are seductive, particularly Antinous, who seems not only to desire Penelope but also to love her. We can understand how easy it would be for a wife to choose someone less complicated than the veteran.

The most devastating scenes in The Return are the reunions. First, Odysseus encounters his dog outside the palace gates. He kneels and whispers the name of his companion, Argos, whose muzzle is streaked with silver. Argos whimpers, licks Odysseus’s hand, and then closes his eyes, dying. For the first time, the camera moves in for a close-up, and we see the king cry, Ralph Fiennes’s eyes enormously blue and ringed with gold.

The initial encounter between Penelope and Odysseus is not a reunion of wife and husband but a meeting of strangers. The way Ralph Fiennes plays the scene, it feels like Odysseus may never choose to reveal himself to Penelope—performed with great skill by Juliette Binoche. It seems that he may simply to choose to keep wandering, the nakedness of homecoming far more frightening than any hand-to-hand combat. But, then, the queen looks closer at this torn man standing before her, and it’s clear she recognizes him.

“Where have you have been since you left Troy,” she asks.

“Traveling. Drifting,” he answers.

“How can men find war but not find their way home,” she demands. There is no more important problem in the film. I suspect that, in every military marriage, this is the central anxiety—that war is alluring, that it calls to us, that we are frequently more drawn to violence than we are to love or comfort.

“Some war becomes home,” Odysseys says.

In Mimesis, Auerbach writes extensively about Odysseus’s reunion with Eurycleia, the nursemaid who has known the king since he was infant. Eurycleia washes Odysseus’s feet in a gesture of hospitality. When she touches the scar on his leg, she recognizes him, knows that this is the same Odysseus she helped to raise. Auerbach is most interested in what he calls “the digression” of this scene, the long recollection in which we see the boar that once gave Odysseus this wound, its fierce tusks, the sound of the animal’s fury as it lunged. But here is no iconic flashback in The Return, only Eurcleyia observing, “That scar. I washed it when it was made. You came in from the hunt.”

Odysseus’s first meeting with his son is particularly uneasy. Telemachus is angry and resentful, and his father wrenched with guilt.

“Who are you,” asks the young man.

“I’m nobody.” Odysseus can barely look at his son. The gap between the hero and the man is something each character in the film is forced to confront. There’s disappointment in the space that lies between myth and the old soldier. The disparity feels like an error, a dropped stitch.

At last, the movie arrives at the showdown in the great hall of the palace. Penelope explains she will marry the suitor who can string Odysseus’s bow and send an arrow through the holes of a dozen axe-heads, just as her husband once did. The bow is the height of a man. The suitors struggle with the task, their palms cut open by the string. Finally, Odysseus asks for a chance. He holds the bow over the fire, passing it across the flames so that the wood begins to soften from the heat. He threads the bow through his legs and bends back the wood. When he plucks the string, it makes a note of music. The camera follows the arrow’s straight course through the arrowheads, its path linear in a way that Odysseus’s journey has never been. Then the killing starts. By the end, Odysseus is covered in blood. The camera doesn’t linger on the violence. No one gets a hero’s monologue.

After that, there’s a shot of the ocean. The light is brighter, the film’s palette shifting from grays to pinks. Penelope cries at what she has seen her son do. “A slaughterhouse—after all these years of holding onto peace.” What follows is the reunion between husband and wife, both equally undisguised now. The film’s closing shot is of open water and a small boat floating in deep solitude on the horizon. War seldom leaves a veteran alone. It returns. It calls the soldier back.

Many years ago, during another long deployment, I sat in my therapist’s office and spoke about his absence. I was so tired of loneliness. Often I wished to unweave my marriage as if it were a piece of cloth on a loom.

At the time, I was suffering from the symptoms of what would eventually be diagnosed as a disorder of the inner ear. My hearing often felt as if it were filled with water.

In the therapist’s office, I could barely hear my own voice. My ear was drowning with the sound of the sea. I couldn’t remember the color of my husband’s eyes. Were they green or brown? How long since we’d slept in the same bed? My husband hadn’t witnessed the horrors of Troy; the cost to our marriage had less to do with the battlefield than with his years of absence, so much distance. Near the end of The Return, when Penelope rinses the blood from Odysseus’s skin, the movie’s message is clear: the intimacy of marriage can only occur if the soldier has been cleaned of violence.

Every week, those fifty-minute conversations in my therapist’s office turned and twisted. I thought of Odysseus, whose mind is as winding as is his journey back to Ithaka. His thoughts tangle and knot. I sat on a couch the color of sand, a box of tissues beside me, and wandered through my own thoughts. “Did you know,” I asked my therapist, “that the words ‘trauma’ and ‘thread’ share the same ancient root?” Sitting there, my fingers found a piece of yarn come loose from the cuff of my sweater. If I pulled, something would unravel.

Jehanne Dubrow is the author of three books of nonfiction and ten poetry collections, including most recently Civilians. Her craft book, The Wounded Line: A Guide to Writing Poems of Trauma, will be published by University of New Mexico Press in November 2025. Her work has appeared in New England Review, Ploughshares, and The Southern Review. She is a Distinguished Research Professor and a Professor of Creative Writing at the University of North Texas.