by Anna Edwards

I first discovered Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita when I was 16, drawn to it by its electric amber cover, illustrated with a large, grinning, anthropomorphic cat. The book is filled to the brim with mischief, and I would later learn that the cat on the cover was Behemoth, the gigantic talking cat that follows the devil around on his escapades in the city of Moscow. The sharpness of the novel would be something I would aim to replicate within my own creative writing, immediately referencing the first chapter for inspiration, in which two characters are (first, unknowingly) greeted by the devil in human form. I loved imagining the devil, Professor Woland, arriving in Moscow and causing mayhem and disorder. The smirk on his face, and the disbelief and incredulity written across the inhabitants of the city that are misfortunate enough to meet him. The question of morality, the world becoming surreal, the absurdity of his sudden emergence. Years later, I felt I saw a moment of Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel materialise in front of me in the form of Hieronymus Bosch’s 1502 painting The Conjurer.

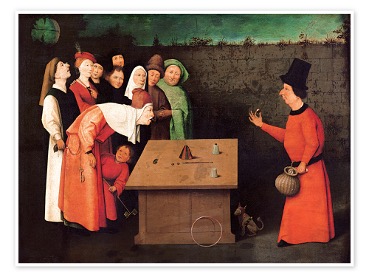

In it, an unlucky targeted subject stares dumbfoundedly at a street magician, with his jaw hanging open in disbelief. He is bent forwards at right angle to inspect the magician closely. The titled conjurer is performing a magic trick, and there lies the sneakiest and most subtle smirk on his face. His fingers are agile, as he clasps a ball the viewer can only assume to have been once hidden. The gobsmacked viewer in the crowd cannot believe his eyes; his expression similar to my own when I see Dynamo on television. Meanwhile, his purse is being pocketed by a thief, who may be working alongside the magician, perhaps a member of his entourage. When observing the painting I imagine the aftermath: the exasperated figure wandering down the street muttering to himself about the sorcery he has just witnessed, only to realise too late that the weight of his money bag is non-existent, it has now travelled far into the ether with the sticky fingered rascal who had his eyes on it from the beginning.

It makes sense to me that this painting is kept in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a commune just north of Paris where I spent a year living when I was 20. I moved close to Paris, charmed by the way I had read about it in books and seen it in films. In a way, I moved there due to my own misconceptions and the belief that its magnificence would solve all the questions of my life. I had taken Bulgakov’s novel with me too, tucked tightly under my arm. Both book and painting have caused much amusement for me. The gaping face central to Bosch’s piece, the sheer cheekiness of it all! The very base of it is laced throughout Bulgakov’s novel.

Bulgakov’s devil leaves no man or woman unaware of his sudden presence. Disguised as the character of Woland, he is a scheming man, who converses with and tempts various characters throughout the book with his charm, insight, and magic. He pulls a blind eye over the inhabitants of Moscow, much like Bosch’s Conjurer figure, highlighting the deceptive world we live in that is so often concealed under the guise of proposed magic. The action is forced upon us in Bulgakov’s novel by the upfront dialogue and vivid scenery, and in Bosch’s painting by the plain brick wall that pushes the scene closely to the viewer. Both comment on the evil that prevails (the devil and his spells; the thievery of not only the man’s purse, but his dignity).

For me, the novel and the painting comment on our blindsightedness to the trickery that exists amongst the world. While the political themes and inspection of moral, and religious notes are what make Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel so paramount, what undoubtedly had me returning to it over and over again was its sharp and addictive humour. I have not read a book that has made me laugh out loud as much as this one did. So dry and poignant it is, and so wonderful at representing people in their prime naïvety, being misled and made to look like a fool — yet also, it serves as an insight into how this very naïvety is what makes us human. What makes The Master & Margarita so humorous is that it does not shy from showing humanity’s capacity to be tricked, which can also be said for Bosch’s painting. Of course, Bosch’s most well-known painting is his depiction of heaven and hell in The Garden of Earthly Delights. While the scenes in this panelled painting are fantastical, dreamlike, and strange, it is perhaps the basic humanity shown in The Conjurer that makes it the most obvious representation of the duplicity of the world we live in.

I return to The Conjurer and The Master and Margarita for their rawness, and the liveliness of the scenes they portray. The emotions written across the faces of Bosch’s figure are brilliant. There is so much conflicted emotion, wonder, and stark contrast between the known and the unknown. Even the young child standing beneath the targeted man cannot help but grin in delight at what is unfolding. The study of the painting and the novel allows me to reconsider the world around me, and judge how much of what I see is true. We can never be fully aware of deception, or how much of what we consume is an illusion. To find humour in this brings light to our own fallbacks, yet it also serves as a reminder to us that we must challenge everything we see.

Anna Edwards is a fiction writer and art lover from the North East of England. After studying English Literature in Manchester, she went on to study Creative Writing at York St John University. She currently has two short fiction pieces published in York Literary Review and Beyond the Walls anthologies, and she is working on her first novel.