by MaureenTeresa McCarthy

Why Mary, I almost said out loud. Of course it’s you. Mary Lennox of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden stood before me on the page, a vine covered fence beside her and a shadowed house in the background. The painting wasn’t really Mary, but Alice in the Lane by American impressionist Lilla Cabot Perry. I’d read The Secret Garden as a child, more than once, and had often wondered about Mary and what became of her. Now here she was, and I had no idea if Perry had ever known Burnett’s work, though it was certainly possible. Burnett was famously popular in her time, and now The Secret Garden is a childhood classic. Perry was known in the circle of early impressionists, though she is often overlooked today.

Mary/Alice looked much as Burnett described her, in a soft summer dress and floppy sunhat, with eyes cast down and lank hair. Mary Lennox lost both her parents and all she had known in the British colony in India during the last days of the Empire. She had been a neglected child – her mother a beautiful woman too busy for time with her daughter, her father often absent. Both had died suddenly in a cholera epidemic. Ten-year-old Mary was sent home to England to live with an uncle she had never met in a house she had never seen. The house was nearly empty, many rooms closed off, as her uncle traveled often. For the first time in her life, she was left to herself. The few servants were her only company. She had never dressed herself or walked out alone. Yet she comes forward, wandering the lane. Shadows and house loom in the background, as she reaches for a red blossom climbing the wall beside her.

Perry’s work brought Mary back to me, as I had always thought of her, centered, the focus of the book, as she is the focus of the painting. The story does begin with her, and in many ways it is a coming of age novel. Mary is a sheltered child, confined to her household in India without other children. Her nurse is charged with keeping her quiet and out of sight. She learns to read but is almost completely unaware of the world beyond the gates.

Sent back to England, traveling with strangers, she is forced in upon herself. At Misselthwaite, her uncle’s house, she begins to explore a world she has never seen: wind and wide blue sky and endless moors. She learns that servants are real people who can be friends. She ventures down the empty halls and into closed rooms in the nearly deserted house, and discovers an invalid cousin, Colin, whom she never knew. The book shifts then, as it becomes the story of Colin and his absent father and the lost garden. The story ends as father returns, and he and Colin unite outside the garden. Mary is there, she is the one who found the garden door, but she is hidden inside the garden walls.

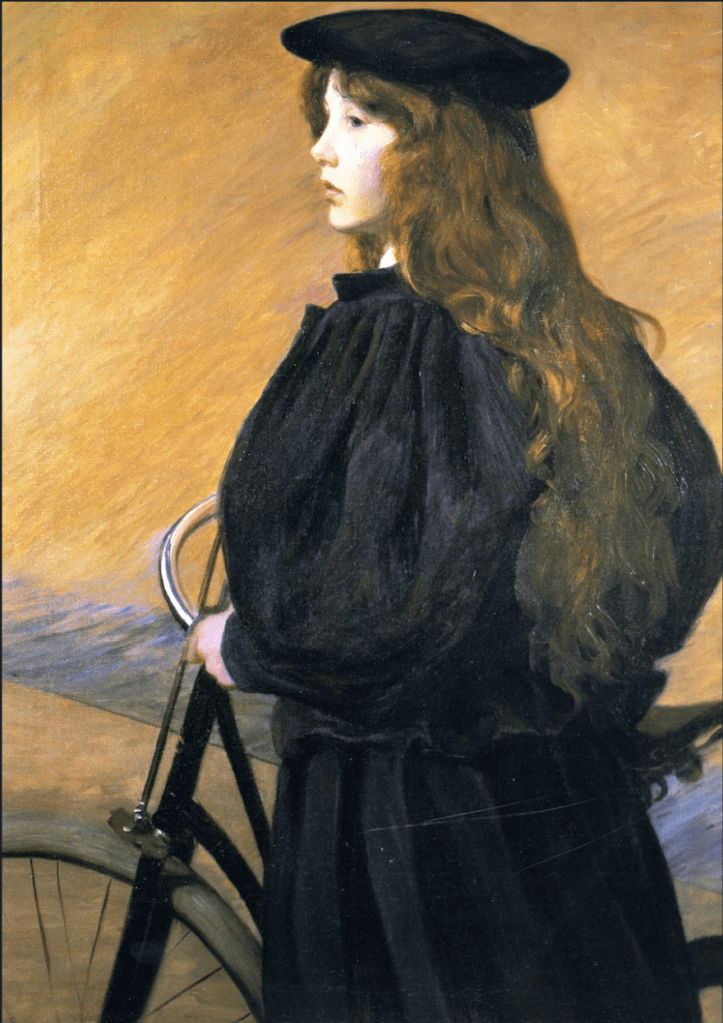

Colin is now strong and healthy, heir to the estate. In that world of upper-class Britain, he would soon be off to school. Mary might have a governess or attend a local school. But outside the text, in Edwardian England, war comes ever closer. Both lives would change. I don’t know how Mary would fare, or Colin either. But paging forward in Perry’s work, I meet Mary again, now as Young Bicyclist. This Mary, all in black, holds the bike upright and stares ahead of her. Her hair is thick and lustrous now; she is a young girl on her way into the world. Once the men and boys left for war, women and girls left the house and managed fields and shops and wartime economy. The quiet golden garden days ended, though Burnett does not take her novel that far. Misselthwaite Manor might even have been turned into a hospital, as many country houses were. Mary, who had already lost one world, would probably volunteer for the war effort, and could certainly have been a courier. She would have ridden her bike, carrying urgent messages, while around her English village life changed forever.

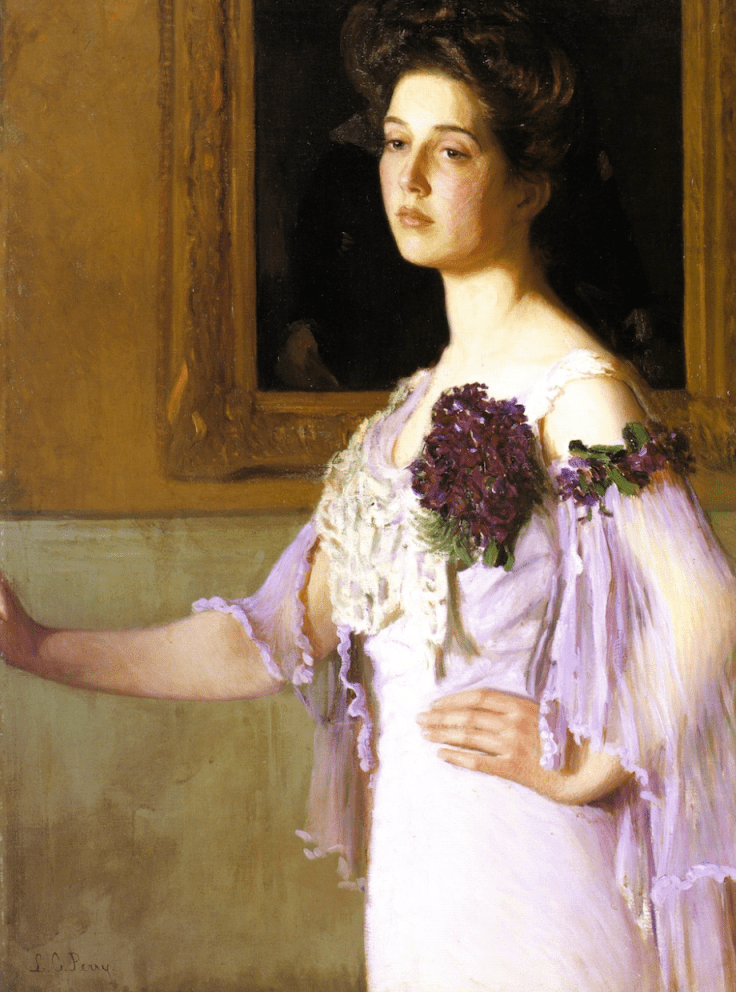

She might have lived on, a young woman as war ended. Still further in Perry’s work, I find Mrs. Joseph Clark Grew, dressed perhaps for her first dance. Mary could have looked like this. Her hair is up, her lips just touched with color. She wears a lovely pale lavender gown with filmy sleeves, a clutch of violets on her shoulder. Mary would certainly have flowers, violets, for remembrance. She wears no jewelry, no wedding ring. On the wall behind her, a dark past fills a gold frame; nothing is clearly visible. She looks forward, somewhat pensive, for though the past is dark, as in the painting behind her, the future is not clear. So many men did not come home, leaving behind widows and girls who would never marry. Women in post war England were facing a world entirely changed, a way of life gone forever.

And Mary Lennox? Were she truly alive and well, I feel sure that the young girl who traveled halfway around the world as a child, explored a huge and empty house alone, unearthed the key to a hidden garden – that girl survived. She would have grown to be a woman who endured, able to face whatever fate offered. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s novel ended with Mary still a child, but imagining her as a young girl, then a woman, is a gift from Lilla Cabot Perry.

MaureenTeresa McCarthy has published poems and essays in Bloom Later, Civilization in Crisis, Comstock Review, Months to Years, PenWoman, PlumTreeTavern, Tiny Seed, Writing in a Woman’s Voice, and elsewhere. Her work focuses on nature, imagination and myth. She has lived and written in California, Europe, and Mexico, but is at home in the Finger Lakes of central New York.