by Kimmo Rosenthal

Connections between the artistic goals of poetry and painting have a long history.

The Chinese described painting as poetry without words. René Magritte is quoted as aspiring to be a poet with the paintbrush, inverting the Roman poet Horace’s apothegm centuries earlier, ut pictura poesis, that poetry should aspire to painting. Wallace Stevens, writing about the relations between poetry and painting, asserted that in both the imagination always makes use of the familiar to produce the unfamiliar, while addressing the state of tension lying at the heart of our daily existence due to the balancing act between reality and the imagination.

In a moment of fortuitous happenstance, I found myself simultaneously discovering a painting and reading a poem that spoke directly to each other, not only in subject matter but in mystery and allure, despite being created over three centuries apart.

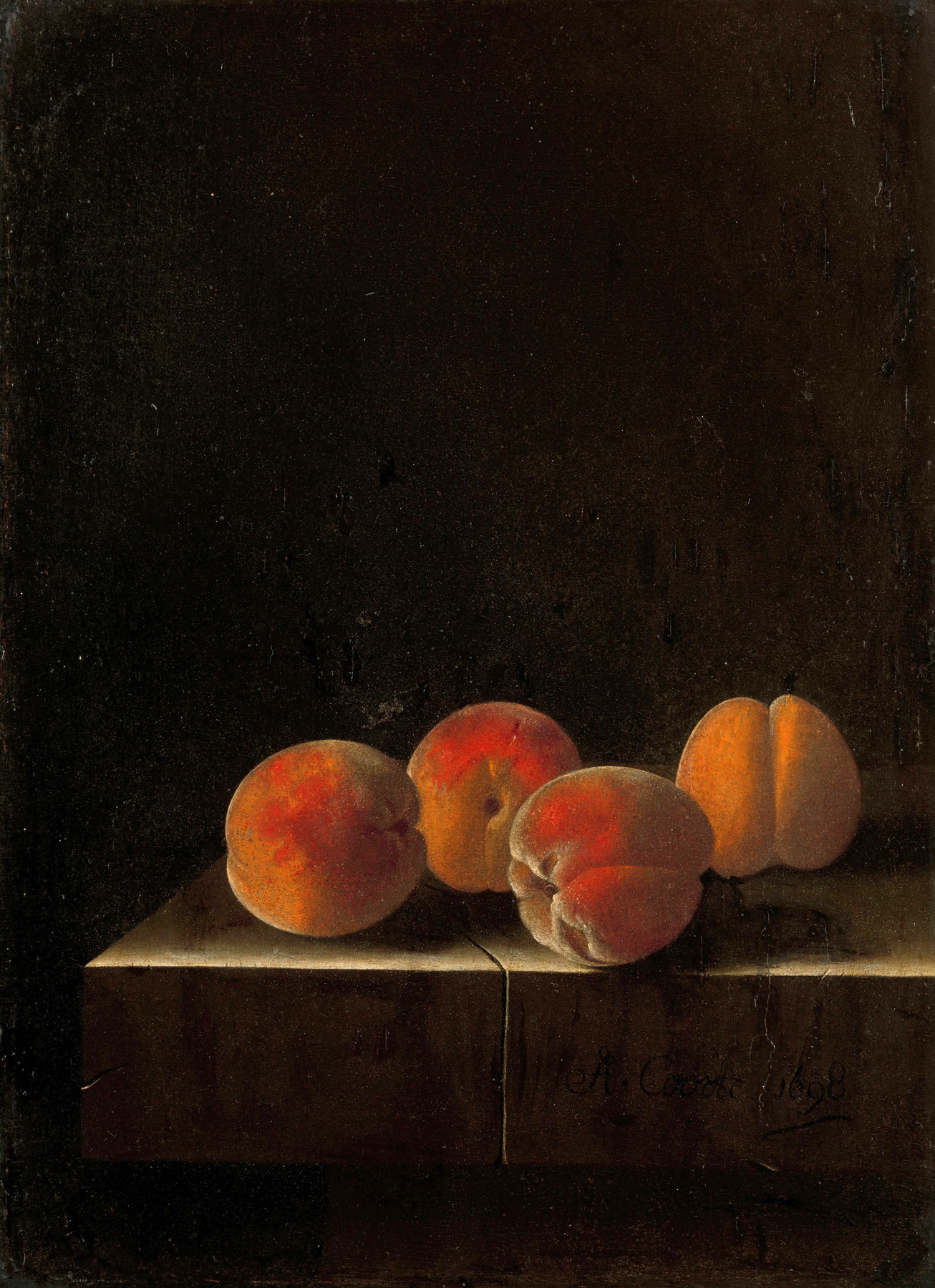

One of the manifold pleasures of viewing art is when a painting that seems to require but a brief moment’s consideration keeps drawing one’s gaze back. Such a moment occurred near the end of Benjamin Moser’s book on the Dutch Masters from their golden age of painting. Having marveled once more at the tenebrous interplay of light and dark in Rembrandt and the sumptuous luminescence and perfection of Vermeer, I was surprisingly enthralled by what, at first glance, looked to be a rather ordinary still life of peaches by Adriaen Coorte, a name unbeknownst to me. Looking more intently, the painting turned out be something quite beyond the ordinary; in some ways it seemed almost modern, belying its dating to the late 1690’s. The peaches looked suspended, as if hovering over the table in a mysterious light source emanating from lower on the left – (a candle on the floor?) – surrounded by an exceedingly dark background reminiscent of, but even darker than, the backgrounds of Rembrandt. Upon searching for the name of the painting, I discovered the fruit in fact was apricots rather than peaches. The painting, from 1698, is in the Rijksmuseum and is entitled Four Apricots on a Stone Plinth.

I found myself thinking of the painting in the context of Rembrandt’s self-portraits with Rembrandt’s visage replaced by the apricots, which looked as if they might have been painted by Vermeer. These apricots were bursting with life, fleshy and brightly luminous, and yet the mysterious light source highlighting a crack on the table, or should I say plinth, seemed incongruously faint to create such vibrant oranges and yellows. How could these apricots be bathed in such beautiful light in the midst of this melancholy, benighted background where absolutely nothing else in the room is visible? What was the artist’s intention?

I agreed with Moser’s assessment that Coorte “infused fruit with mystic qualities.” There is something otherworldly and magical about Four Apricots on a Stone Plinth. At the time of the painting still lifes were considered a lesser genre, lacking the gravitas of portraiture, landscapes, or paintings filled with religious symbolism and classical allusions. Chardin, the apotheosis of still life painters, was accused some fifty years later of laziness and wasting his talent. This criticism of Chardin brought to mind a great ekphrastic essay by Proust about him, wherein much of what he posits could well be applied to Coorte.

Proust uses adjectives such as arresting and vital as he speaks of the delicate brushwork and colors evoking the beauty and divine quality of “the unnoticed life of inanimate objects.” I can mentally visualize Coorte’s painting when Proust describes, in his inimitable way with language, “swelling peaches, rosy as cherubs, inaccessible as the gods of Olympus.” His discussion of Chardin’s witchery and mystery evokes the symbolism of fruit.

Peaches, with their beauty and succulence, and, since they are so similar, we can include apricots, have often been depicted in mythology, whether Chinese or Greek, as the fruit of the gods. For the Greeks, they were associated with Hera, representing love and abundance. How might the images and feelings conjured by Coorte’s painting be best expressed in words, considering the inherent difficulty in doing so?

At the time I encountered Coorte’s painting, I had been reading the poetry of Nobel laureate Louise Glück. I was especially interested in later works such as The Seven Ages, written after Glück had turned fifty, which is a meditation on aging and facing approaching mortality while interrogating the past. It addresses the unrelenting passage of time with feelings alternating between melancholy resignation and the need for acceptance, while acknowledging the beauty in the world and the hope that there are meaningful experiences yet remaining. A line which resonated with me and encapsulates the overall mood is: “after long life is one prepared to read the equation.” What are the two sides that need to be reconciled? Does this reading of the equation manifest itself in Coorte’s painting, where the fruit beckons amidst the inconsolable darkness of the background, exerting a pull towards life suggesting the possibility of consolation? Glück’s poem “Ripe Peach” seems to directly address this. It echoes Stevens’ claim regarding making the familiar unfamiliar and, upon rereading it, a portal in my mind’s eye opened up on Coorte’s painting.

In Glück’s work everyday things and experiences carry a weight, and her straightforward, limpid prose needs to be read circumspectly and not taken at face value. For Glück, the fruit represents the earth and the sweetness and beauty of our lives, and yet this ephemeral “disappearing sweetness surrounding the stone end” leads to the pit, the hard center left over, which represents the mind, with its reimagining, analyzing, and trying to come to grips with the inexorable march of time.

In the center of the mind / the hard pit, / the conclusion. As though the fruit itself / never existed, only / the end.

It is the realization of this passage of Time (to capitalize it à la Proust) and the approaching end that haunts Glück’s work.

The night sky / filled with shooting stars. / Light, music /

from far away – I must be / nearly gone. I must be / stone, since the earth / surrounds me

And, yet, the poem concludes with, as alluded to above, an acknowledgment that there is still beauty in the world to be appreciated, even in one’s vesperal years.

There was / a peach in a wicker basket. / There was a bowl of fruit /

Fifty years. Such a long walk / from the door to the table.

I see this reflected in Coorte’s painting with the luscious apricots filled with vitality surrounded by the exceedingly dark background. The table represents an invitation to participate in the simple pleasures left, symbolized by the apricots, that can still be sustaining and meaningful. The painting seems to herald the poem written centuries later, addressing the emotional ambivalence we feel as we age. In a room with the dark gaining, one can still reembrace the world.

In “The Quince Tree,” also in The Seven Ages, Glück reflects on the past and the whole of her existence while looking out at her all-too-familiar yard and in the brief compass of that moment is struck by a Proustian revelation – even the little quince tree had a “weight and meaning almost beyond enduring. In its grandeur and splendor, the world was finally present.”

This is the grandeur, splendor, and strange beauty of the four apricots on a stone plinth.

Louise Glück, “Ripe Peach” and “The Quince Tree” in The Seven Ages, in Poems 1962-2012, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2012.

Benjamin Moser, The Upside Down World: Meetings with the Dutch Masters, Liveright, 2023

Marcel Proust, “Chardin,” in On Art and Literature, DaCapo Press, 1997

Wallace Stevens, “On Poetry and Painting,” in The Necessary Angel: Essays on Reality and the Imagination, Vintage Books, 1951

Kimmo Rosenthal, after a long career in mathematics and teaching, has turned to writing with over thirty literary publications and a Pushcart Prize nomination. Recent work has appeared in Tiny Molecules, The Fib Review, The Decadent Review, After the Art, Tears in the Fence, and BigCity Lit.