by Cheryl Sadowski

Perhaps more than any other season, summer invites drama. Time gathers and thickens with the heat of a late afternoon storm, or a tangy barbecue sauce. The temperature is just right, conditions just so … for a new friendship, an unexpected encounter, an impossible romance.

I met my best friend, Beth, during the summer between second and third grade when I accidentally jumped directly on her in the community swimming pool. I remember the way her long blonde hair swayed like reeds in water as she worked fervently to dislodged herself from my (then bony) body and come up for air. We are both 56 now, our friendship having survived and thrived despite the physical shock of that initial meeting.

During another, much later summer, I shared an apartment with three women from southern India spending a semester abroad in the U.S. I will forever associate the sight and smell of turmeric and mustard seeds popping in ghee with the intense heat of that particular July and August, when everything was parched for want of water. To this day my craving for spicy food, specifically Indian cuisine, increases in proportion to the rising temperature.

And I remember a long, lazy summer with my boyfriend of nearly three years, before I picked up and moved to Chicago. We had a sultry, tumultuous relationship: jealousy, big fights, coarse make-up sex followed by fleeting tenderness. After graduating from college, I decided to remain on campus for an indeterminate time. Any discussions my boyfriend and I might have had about our future were subsumed by the afternoons we spent swimming at the lake, drinking and smoking among friends whose high laughter helped to veil our fundamental incompatibility.

The human body internalizes summer. We close our eyes, let the sun warm our face, penetrate our eyelids. Tiny sunspots of color float across the private amphitheater of our brains. In the distance, the low thrum of a lawn mower, the thwack of a screen porch door, bubbles of laughter from a nearby park. The back of our necks and the tips of our fingers tingle as color, heat, and sound swirl about like a kaleidoscope.

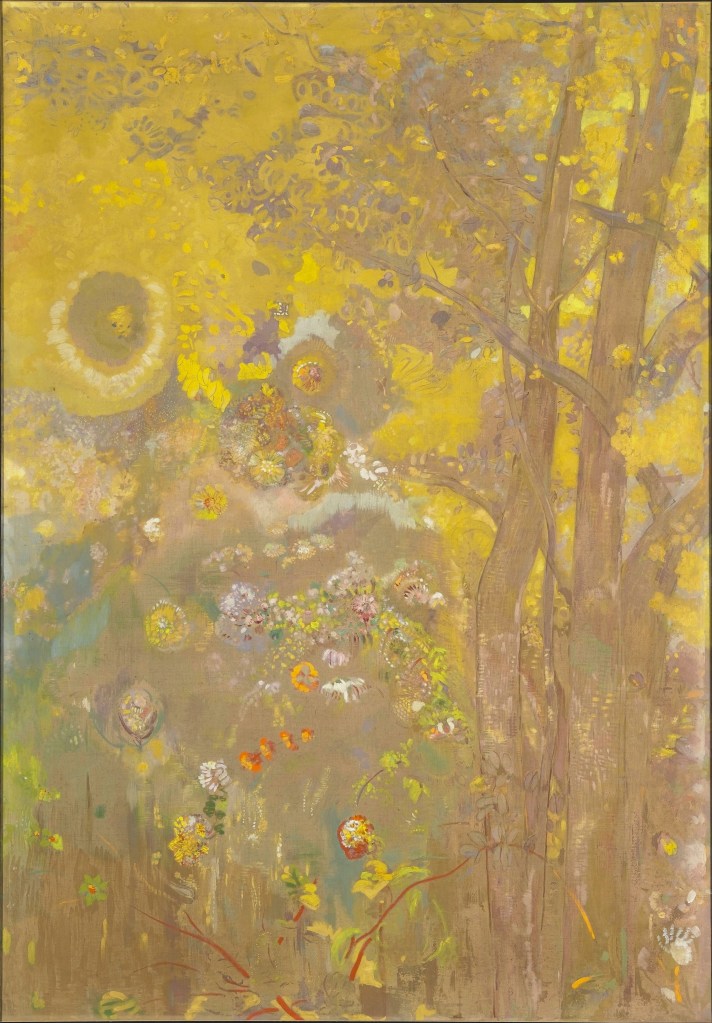

The French Symbolist painter and printmaker, Odilon Redon (1840-1916), captures the psychedelic state of summer in his Trees on a Yellow Background, which I stumbled across online, last year. 2022 was an unremarkable and bleak winter, void even of snow, so I was grateful when the sight of Redon’s surreal painting instantly drew me into summer nostalgia.

He saturates the top two-thirds of his canvas in yellow-ochre, imbuing a swath of hazy heat punctuated by random, mustard-colored corkscrews and circles. Dabs of pale aqua suggest distant water, foregrounded by orange zinnias and Queen Anne’s lace. There is a lava-lamp quality to Redon’s colors, whorls and eddies. They obfuscate, as he himself admits: “The only aim of my art is to produce within the spectator a sort of diffuse but powerful affinity with the obscure world of the indeterminate.”

Upon closer looking, there are few green leaves, and a metallic gray background suggests sadness lurking behind all of those spectacular yellows and golds. This isn’t midsummer after all: Redon is showing us the afterward of summer’s apex as it bends toward autumn, although it’s unclear where in that continuum we are. For who can pinpoint the precise moment when summer ends and fall begins? Or when anything truly begins or ends, for that matter?

In the pitch of summer, even reading is different. Books come to us in unexpected ways. They are left in the far corners of cafes, discarded on benches in locker rooms. They tumble down from the neglected top shelf at a library book sale. Sometimes they arrive shrouded in grace, like the time I found Edith Wharton’s Summer lying abandoned on some immemorable tabletop.

The book’s cover called to me like a siren—the faded outline of a young woman holding a pale rose as she sits in fields of yellow-ochre. She is blended into the meadow with Impressionist brushstrokes, as if she is part of it. I give credit to the marketing minds at Penguin Classics, who manage to combine imagery and author into a bookish temporality that cannot be ignored.

Summer is about a young woman, Charity Royall, whose nascent sexuality is kindled in June, emblazoned in July, and dampened by late August. Despite the bright yellow optimism of the season, she is forever tethered to mysterious, ‘unsavory’ origins as the unwanted daughter of an unwed mother “from the other side of the mountain.” Her adoptive father is appropriately protective, and also meekly in love with her.

Charity is as fiercely protective of the freedom she enjoys in her small household as she is raw in her determination to forge a new and independent life for herself. A quick study of character and circumstance, she begins a romance with a young architect who is spending his summer in the dull town of North Dormer drawing the town’s crumbling, classical architecture.

Wharton’s descriptive references of the Mountain looming in the distance, and of elegantly decaying buildings—including the little, sun-bleached house where Charity meets her lover—permeate the novel with the sense of ending. We anticipate autumn’s mood even as things are just beginning for Charity, who “to all that was light and air, perfume and color, every drop of blood in her responded.”

Somewhat predictably in classic novels of lost innocence, she becomes pregnant and is forced to confront limited options given her particular station in life in turn-of-the-century, rural New England. Wharton veils the power dynamics that fly between Charity, her lover, and her lonely, suffering father, the town’s lawyer, in language fitting for 1916, the year she wrote Summer (and the same year of Redon’s death). But the spartan truths are undeniable as the story presses ahead with its vivid portrayal of sexual awakening blunted by the forces of sexism, classism, and rural poverty.

There is no grand parting, no dramatic farewell, only the ascendency of hope followed by the descent of hope’s end. Her very name is a cruel irony for the young woman whose zeal and ebullience fade into the landscape, like the image on the book’s cover. (Again, Penguin Classics: they get it.)

When I finally left college for good, my boyfriend and I exchanged few words. Our relationship simply faded. There was no real identifiable tipping point, no formal break-up, or bouts of tears. We never talked about how much or how little time we had left together before my father and mother arrived to drive me to Chicago, where they would help me unpack, move into a new apartment, and begin a new life in that bustling city.

But when the temperature is right and the conditions just so, I can close my eyes and recall the light and air of that last summer my boyfriend and I spent together. I can conjure bright yellow turmeric and mustard seeds frying in a pan, and the golden fan of my best friend’s hair. Summer sunspots burst behind my eyelids, and I float amid the yellow orbs of Redon’s painting. Autumn is never far off.

Cheryl Sadowski writes essays, reviews, and short fiction that explore the plain weave of everyday life with landscape, literature, art, and the natural world. Her writing appears in About Place Journal, Vita Poetica, The Orchards Poetry Journal, After the Art, EcoTheo Review, and other publications. She lives in Northern Virginia.