by Daniel A. Hill

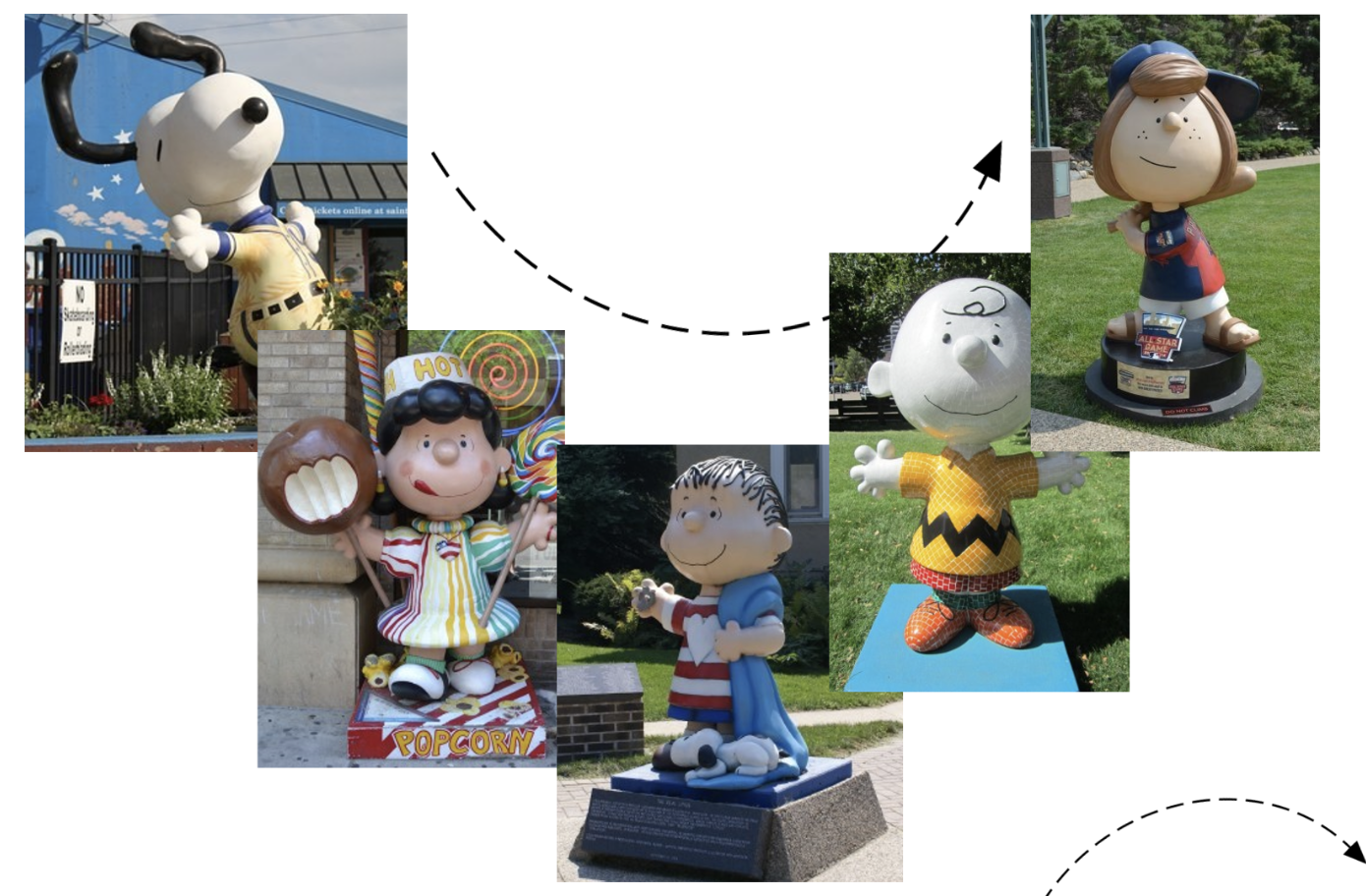

I suppose I could say that I’m writing about Charles Schulz and his venerable Peanuts comic strip series because the guy lived his formative years less than a mile from my house in St. Paul, Minnesota. Or that as a kid I devoured his three-panel portraits of childhood mischief and despair. Neither reason really explains why I’m writing about Charles and Charlie now, though. Instead, to be honest I recently gave a talk at the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California because I’m irked by how his artwork is being remembered given the statues of Charlie, Lucy, Snoopy, Linus and company that I bike by daily during the summer months in Schulz’s hometown.

Those well-meaning statues fail twice over. For starters, they’re too tall. At an average height of five feet, these fiberglass monstrosities would tower over the actual Peanuts gang. Let’s use Snoopy as a barometer here. The typical beagle is 13-15 inches tall at the shoulder, but of course the clever Snoopy can usually be found standing up. Online sources (probably Peanuts devotees) insist that Snoopy stands about two feet tall. Look at any strip where Charlie Brown and Snoopy stand side by side and you’ll see that Charlie is no more than maybe twice the height of his beloved pouch. That would mean Charlie and company may be all of seven or eight years old based on their size. Someone five feet tall, however, is a teenager and not necessarily so easily loved as Schulz’s creations are; doubt me, ask my sister, who saw 13 as the age when each of her six dear children turned into hellcats for the next few years.

In short, these overly large statues force Schulz’s kids to grow up prematurely, which nobody wants—me least of all. I say leave them be in first or second grade forever, enjoying the years before schooling diminishes their creativity. Furthermore, it’s hard to hug a giant. Doubt me, go online to view the many towering statues of dictators like Joseph Stalin or Saddam Hussein that have been toppled after their citizens gained a measure of freedom.

Size aside, the large fiberglass statues also embody a second flaw even more fatal than the first flaw: the Peanuts gang has been transformed into overly happy nitwits. Now I love good humor as much as the next guy. Not by chance do I recite the Czech writer Milan Kundera’s remark: “Don’t trust anyone without a sense of humor. I never met a KGB agent who had one.” Why, I might even go so far as to dare say that having a sense of humor is a recipe for living the good life. Studies show that being happy not only means that, yes, our spirits have been lifted; our creativity improves, too. In group brainstorming sessions, for example, the solutions come more readily and are better on average if you’re all feeling good (which means the boss is absent). Put another way, happiness isn’t a trivial emotion—unless it’s the only flavor being served at the ice cream parlor.

Re-watch “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” which premiered in 1965, and you’ll see animation bathed in gray tones along with some wafting snowflakes and the puniest, most melancholy Christmas tree that you, I or Charlie will ever come across. The Peanuts comic strip is both funny and not in the least funny, and that’s the point. Linus is at once Lucy’s younger brother, Charlie’s best friend, and the ghost of Jean-Paul Sartre. Yes, the groans of French existentialism inaudibly echoed daily right up until Schulz died in the winter of 2000, leaving only his cartoons to carry on.

Step back in time for a moment please, and I hope you’ll see where I’m coming from in linking Schulz to Sartre and even the likely original though unofficial existentialist: the Danish theologian and philosopher Soren Kirkegaard. What do these three men have in common? If I were to answer that question in a single word, I would have to choose abandonment. Kierkegaard believed in God but had to wrestle with the profoundly unsupportive silence with which his prayers were answered. In turn, Sartre didn’t believe in God but was enough of a mystical atheist that he longed for us to become our own saints so that we might best paper over the void of human existence. Then along comes Schulz, who brings the dilemma of being human blissfully down-to-earth by giving us a world in which not only is God as invisible as The Great Pumpkin figure Linus faithfully awaits, there are also no adults around in the Peanuts comic strip to assert moral authority.

What we’re left with is a lack of comfort, and the need to fall back on ourselves. That’s the primary legacy of the Sartre-Schulz version of theology.

Never mind that Schulz never stumbled across Sartre’s world views until the mid-1950s. Or that around then, Schulz found himself being publicly labeled the “youngest existentialist” by the Democratic National Committee in a weird attempt to get the up-and-coming cartoonist to endorse Adlai Stevenson for president. That’s all just a bunch of noise. Silence is the key, as we’re left to wrestle with on a daily basis what we will make of our world through our (in)actions. Good and evil, bravery and cowardliness, are not pre-ordained. Welcome to loneliness and alienation. We’re all damaged goods. The most we can do is care, and try, embodying a psychic legacy that Kierkegaard saw as in place by the age of ten, which Schulz cut in half by settling on age five or six being the point at which we essentially become who we are and will be: “boiling pots on a stove.”

Put another way, in Charlie Brown’s endearingly earnest world uncertainty casts a long shadow. The famous football is always being symbolically as well as literally snatched away by Lucy as proof that realizing fulfillment in life remains an elusive dream. Schulz-the-understated-Midwestern-artist is the polar opposite of an opera star brandishing a melody. He’s a minimalist at his happiest when he’s singing in a minor key. Sartre’s Being and Nothingness was published in 1943. Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot was first staged in Paris in 1953. Sandwiched in between those dates is when the initial Peanuts strip appeared on October 2, 1950, making Schulz something of a Parisian existentialist in exile.

Short and to the point by having no point other than exposing life as it really is (full of doubts and disappointments) was always Schulz’s mission in life. He was a guy born to draw. Everyone other than his parents doubted him. St. Paul high school classmates attending a reunion doubted that Schulz was “that Peanuts guy” until he drew Charlie’s face and figure right there before their doubting eyes. Most searing of all was Schulz’s memory of the sweetheart he sought to marry years earlier, a girl who didn’t even get the chance to refuse him. Her mom stepped in by telling her daughter that Schulz wouldn’t amount to anything. Wave him off. So, Donna Johnson married a local fireman instead and must have noticed, with some dismay, when the debut of Schulz’s first book, Happiness Is a Warm Puppy in 1962, brought the son of a self-employed barber untold millions of dollars.

Unrequited love is, in fact, the storyline that brings unity to Peanuts. Lucy longs for Schroeder, the Beethoven-loving wannabe pianist pounding away silently in Schulz’s handiwork. In turn, you’re also witnessing Peppermint Patty longing for Charlie, and Sally longing for Linus. In other words, Schulz hides the shame of romantic denial by reversing the gender roles. The girls seek out the boys, rather than Schulz seeking Donna.

Nor is girl-courts-the-boy-but-doesn’t-get-him-in-the-end the single grand reversal of gender stereotypes in Peanuts. Anger is typically an aggressive emotion, a matter of seeking to assert control. Men are usually more afflicted by it than woman are. When I used my craft of being a certified facial (de)coding expert by analyzing a slew of Peanuts comic strips, what did I find by studying, in particular, how the characters’ eyebrows and mouths were drawn? Were their inner and outer eyebrows pulled up or down and pinched together? Did their mouths rise in a smile, or were they puckered, downcast or pulled wide in fear? Four of the strip’s main female characters (i.e., Lucy, Peppermint Patty, Marcie and Sally) showed 13% more anger than Charlie, Linus, Schroeder and Snoopy did, and in another twist on stereotypes that female gang of four also showed five percent less fear (of NOT actually being in control) than did their male counterparts.

As I told the audience at the Charles M. Schulz Museum, Happiness Is a Warm Puppy paradoxically enough didn’t make Schulz happy despite the money it earned. For starters, the corny, reductive title wasn’t his idea (and he fought against it); the publisher devised it as the moneymaker that it proved to be. Moreover, the title artificially narrowed Schulz’s emotional palette and took the spotlight off Charlie Brown. Later on, Beethoven’s long lost kid brother, John Lennon, mocked the book’s title and the National Rifle Association at the same time by singing that actually “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” on The Beatles’ White Album. Was Schulz duly mortified? I suspect so, given that Schulz was a serious artist himself and subsequently became more downbeat in portraying his characters.

As a facial (de)coder, I couldn’t help but notice that only Snoopy is ever exuberantly happy for long (and in doing so can be oblivious to others). Marcie is slightly happy. The other, supporting cast members in Charlie’s gang all fall into negative emotional territory on average. The volatile Lucy swerves from happiness to anger and fear, only to circle back to (self-deluded) happiness ever so briefly. Linus is riven by fear. Schroeder and Sally are indignant. Peppermint Patty can succumb to smirks, and so on.

The point I’m ultimately trying to make here is this: during the 1970s, i.e., the decade after the runaway, financial success of Happiness Is a Warm Puppy, Schulz penned cartoons that were his most emotionally negative ever—by far—and never looked back. In my patented facial coding scoring system, the Appeal score indicates the overall positive or negative valence of what I’m seeing (in this case) on (Peanuts characters’) faces as opposed to real, living human beings. Note the progression. Contrast the 1950s to the 1960s as Schulz’s Peanuts appeal score climbed from 1.9 to 3.5 before falling to -7.3 in the 1970s, followed by -5.9 in the 1980s and finally -5.1 in the 1990s. As best I know, the word “happiness” never graced the cover of another Peanuts book until after Schulz had died.

What emotions did Schulz gravitate to as an artist? I suggest we look to his alter ego for the answer. Charlie is most at home with the emotions of disgust and sadness, which he exhibits more than any other character in Peanuts. Rejection (disgust) and loneliness (sadness) mark Charlie and give him his humanity. “Good grief!” is Charlie’s signature comment, a way of signaling that he’s dismayed and maybe even depressed by the vagaries of human nature. Grieving was good for Schulz though because it invites reflection and empathy, the hallmarks of great art.

It’s a very American thing to emphasize happiness blindly over all other emotions. Thomas Jefferson did so by insisting we have been endowed with “certain unalienable Rights,” among them “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Campaigning in 1988, George H. W. Bush insisted that “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” by Bobby McFerrin was his favorite song. In 2006, the movie “The Pursuit of Happyness” starring Will Smith ends with a former homeless man owning a multimillion-dollar brokerage firm—proof positive that William Dean Howells was on track when he said that what Americans want “is a tragedy with a happy ending.”

Sticking to his gun, i.e., his drawing pens, Schulz didn’t accept cheap lugubriousness. Most of his comic strips end forlornly. So, those tall, fiberglass statues always and forever adorned with smiles are a travesty. And so was the opening of Camp Snoopy in Bloomington, Minnesota’s Mall of America. That vast indoor amusement park (since renamed and under new management) promised the opposite of reflection: thrilling distraction. As such that indoor park thereby inadvertently reinforces the validity of the Sartre-Schulz school of forsaken yearning, which is that the only form of consciousness people come even close to being adept at is Charlie Brown style self-consciousness. In other words, forget about plunging rollercoasters. We’re already got our hands full trying to navigate the world atop our own shoulders, each of us just as baffled as the next person in line ready to take the ride of their life.

Daniel A. Hill, PhD, is the author of 10 books including First Blush: People’s Intuitive Reactions to Famous Art. Dan has delivered lectures based on insights using eye tracking technology for the Tate in London, the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, and other art museums and academies across America. Previous essays have been noted with honor in three editions of The Best American Essays.